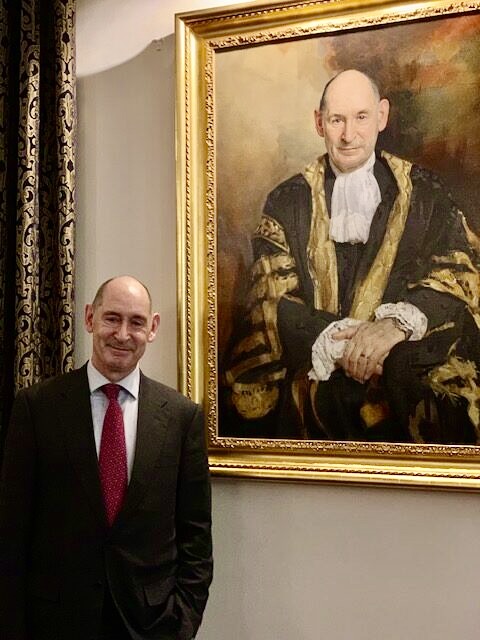

Foreword by Kevin Bazeley

Before his death on 6th of May 2025, Lord “Terry” Etherton GBE KC PC, wrote a lecture telling of the legal activities to lift ‘The Ban’ and his ultimate involvement in the LGBT Veterans Independent Review

Sadly his death meant that Lord Etherton never got to deliver that lecture himself. Instead in June of 2025, his friend and colleague Lord Michael Cashman CBE (Himself a founder of Stonewall and instrumental in the original support to the legal challenge) gave a posthumous delivery of the lecture to a small gathering in the House of Lords.

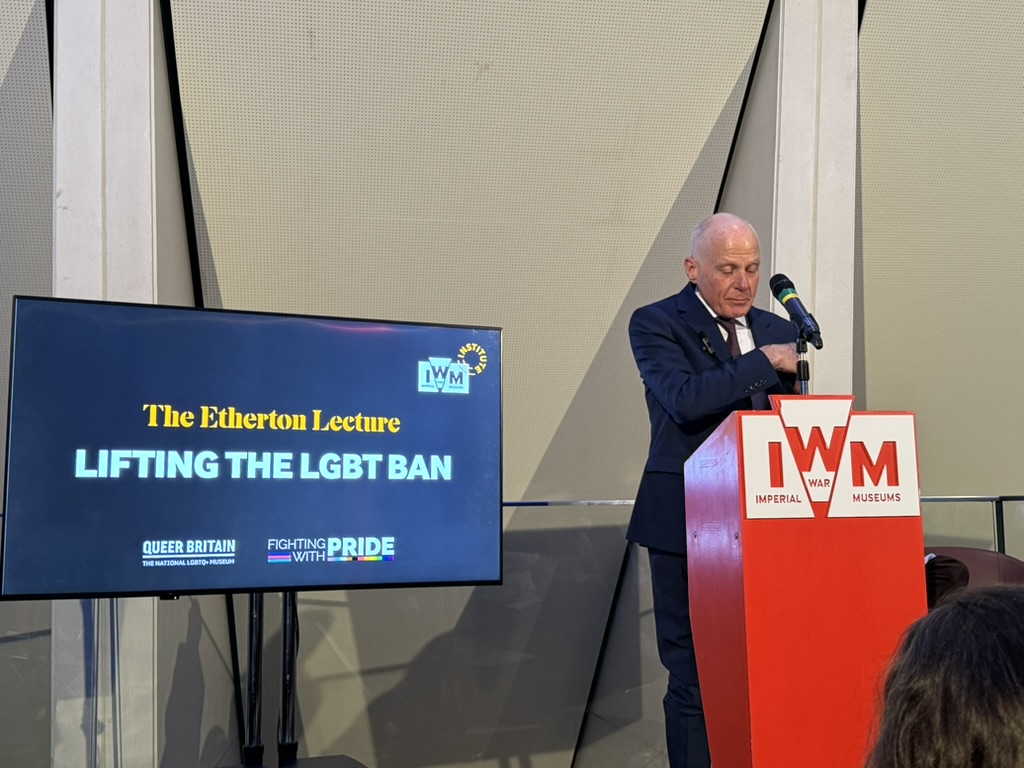

With the kind permission of Lord Etherton’s husband, Andrew Stone, Lord Cashman again delivered the lecture at an evening event in the Imperial War Museum London on Thursday 15th January 2026 recognising the 26th anniversary of the lifting of ‘The Ban’

The lecture was another part of the healing journey for those impacted by the ‘Gay Ban’

As well as Lord Cashman to deliver the lecture itself there was a panel of guests for a discussion to follow. Edmund Hall, Chair of the Board of Trustees for Fighting With Pride (FWP), Caroline Paige MBE co-founder and joint CEO of FWP for the first part of its history and Lisa Power MBE also a founder of Stonewall

A capacity crowd of Veterans who had been impacted by the ‘Ban’, their partners, family and friends plus representatives of the organisations & people that got us where we are today; Rank Outsiders, the Armed Forces Legal Challenge Group, the ECHR4, FWP Trustees gathered to hear their legal history spoken of on the public stage.

The event and discussion was compered and moderated by the actor, author, podcaster and LGBTQ+ activist, Russell Tovey.

The video of the Lord Etherton Lecture is available here

The full text of the lecture is provided below

With thanks to the Imperial War Museum London for hosting and recording the event.

The Lord Etherton Lecture:

Lifting The Ban

By The Right Honourable Lord Terrence Etherton GBE KC PC

“Terry”

With special thanks to his Husband, Andrew Stone

In May 2021 my PA received a request from Leo Doherty MP, the then Minister for Defence People and Veterans, to meet me.

I was rather perplexed as I never served in HM Armed Forces and had never had any association with them

When the Minister arrived in my room flanked by two officials from the MoD, he announced with a flourish that he came, not on his own behalf, but rather on the instruction of the Prime Minister. That was good advocacy although, I fear, not entirely correct.

He asked me whether I would be willing to undertake an independent review into the service and experience of LGBT veterans who served in the Armed Forces between 1967 (when homosexual acts between consenting adults in private were decriminalised by the Sexual Offences Act except for those serving in the Armed Forces) and 2000 (after the European Court of Human Rights had determined that the Ban on the service of LGBT people in the Armed Forces was contrary to the European Convention on Human Rights and shortly before the Ban was formally lifted in January 2000).

I explained to the Minister that I had never been involved with, nor ever had any association with, the Armed Forces. I added, however, that I had served in the CCF at my secondary school (which was compulsory) and I had received a commendation for the state of my uniform: an entirely appropriate objective for a gay man. He replied that he could think of no better reason why I should carry out the review, as requested.

After some negotiation over my terms of reference, I decided to accept the request to carry out an independent review.

Administratively, the situation was rather confused as, in addition to the Minister for veterans in the MoD, there had been created an Office for Veterans affairs to lead the cross- government delivery of the veterans strategy action plan 2022 – 2024. The OVA was part of the Cabinet office. The broad objective of the OVA was to achieve the government’s vision to make the UK the best country in the world in which to be a veteran. The Plan included the commissioning of an independent review into the impact that the pre-2000 Ban on homosexuality in the Armed Forces has had on LGBT veterans in present times.

The OVA was headed by Johnnie Mercer MP. In the event it was the OVA which assumed primary oversight of the Review, save in respect of financial reparations.

I acted on my own as the Reviewer, but I had the assistance of a small and enthusiastic secretariat. The person in charge of the secretariat was Rachel Seddon, who was outstanding. I also had a board of advisers covering different aspects of the matters in the Review.

The call for Evidence was launched on 15 July 2022 and ended on 1 December 2022. There were 1,128 responses to the Call for Evidence. Many were substantial. One extended to over 50 pages. I read every testimony, each of which was anonymised.

Of the LGBT veterans who responded and stated that they had been dismissed or discharged due to the Ban. 41% identified as male, 59% identified as female, 2% identified as transgender

44% of the LGBT veterans who responded to the Call for Evidence indicated they were forced or compelled to leave the service through unofficial methods or actions or due to general hostility towards LGBT personnel. 35% identified as male, 60% identified as female and a further 5% identified as transgender male or female.

The ratio of females to males who identified as homosexual or were perceived to be such and responded to the Call for Evidence is notably high at 61:39. I shall return to this later. There are inadequate data to estimate with any accuracy how many officers and other ranks were discharged or dismissed on grounds of sexuality. Figures vary between 2,400 and 2,800 over the period 1967 to 2000..

My appointment was formally announced on 22nd of June 2022.

The Ban can be described as a policy that no person subject to military service law who was gay, lesbian, transgender due to gender dysphoria, or was perceived to be such, even if they were not in fact, could be or remain a member of the Armed Forces. It made no difference that such military personnel never engaged in same-sex sexual relations and even though they were not aware of being gay, lesbian or suffering from gender dysphoria when they join the Armed Forces, sometimes when only 15 years of age.

There were a number of different categories of people adversely affected by the Ban. There were those who were dismissed, following a court martial, or were administratively discharged pursuant to what were then the Queen’s Regulations (now the King’s regulations), a code of regulations affecting the military which are outside the civil law.

There were also those who could not take the strain and stress of continually hiding their sexuality, and so resigned or did not extend their contract. The policy was not enforced uniformly across the Armed Forces but, where it was enforced, it was usually enforced in a rigorous and often brutal way with long-term damaging consequences, many of which have blighted the lives of affected personnel to this day.

At the heart of the Review, leading to the Final Report, were the statements of those who are victims of this overt homophobic policy. The statements of those who gave evidence to the Review gave shocking evidence of a culture of homophobia and bullying, blackmail and sexual assaults, abusive investigations into sexual orientation and sexual preference, disgraceful medical examinations, including conversion therapy, peremptory discharges, and appalling consequences in terms of mental health and well-being, homelessness, employment, personal relationships and financial hardships

Over the years since the Cold War, many justifications for the Ban have been put forward by MoD officials, senior officers and others. Ultimately, the sole justification was that sexuality was a threat to the effectiveness and efficiency of the Armed Forces. That assertion of the threat of homosexuality to operational effectiveness and efficiency, reduced to its core, was based on the notion that, because heterosexual military personnel did not wish to serve with known or suspected homosexuals, it would undermine the efficient and effective operation of the Armed Forces to require them to do so. This had nothing to with any assumption that homosexual men and women were themselves less physically capable, brave, dependable and skilled as heterosexuals.

My overall conclusion was that, after the Sexual Offences Act 1967, the continuation of the Ban in the Armed Forces was the product of a deeply ingrained policy sanctioned and enforced by the MoD and the senior ranks within the services.

The institutionalised homophobia of the policy of the MoD and senior ranks of the Armed Forces in effect gave a free hand to obsessive and usually abusive, brutal, and bullying investigations by the Special Investigations Branch for each of the three services throughout the period covered by the Review.

Where one person had been identified as a potential suspect, it was frequently the case, especially with women, that raids would be made on their service accommodation with all those present being subjected to a search. In common with all searches of LGBT personnel the key focus of the search was photographs, personal letters and diaries in addition to any other physical evidence which might show participation in homosexual activity.

Evidence was given to the Review of the covert surveillance of gay pubs and other venues in order to identify any military personnel. This took the form of both checking CCTV and the presence of SIB members in civilian clothes.

Details of number plates of cars identified registered to military personnel, and which were parked at places where gay men were to be found were passed by civilian police to the SIB.

The SIB conducted extensive surveillance operations against military personnel who were suspected of being homosexual. The Review was told of one operation which involved several teams of undercover military police conducting 12 weeks of surveillance of three fighter pilots who shared a house together off base. Ultimately, each of them was discharged, not because of any service offences having been committed and without any disciplinary charges having been made, but merely on the ground that they were homosexuals.

Although many of the youngest recruits, who were teenagers (some as young as 15) were not conscious of their sexuality on joining the Armed Forces, there was no one with whom they could have a supportive and safe discussion about their growing awareness of their sexual identity as gay, lesbian or bisexual or coming to terms with an emerging sense of gender dysphoria. Any such discussion carried the overwhelming risk of disclosure to those in command. Replies to the Call for Evidence give examples of young personnel who talked in confidence to a military friend or to a military padre who promptly reported the conversation to the commanding officer. There is nothing to suggest any revelation of sexual activity. They were simply young people who were seeking help in relation to the confusion experienced by many youngsters as they become aware of their sexual and gender identity.

The Review was told that betrayal by the chaplaincy and also medical officers was a common cause of investigation and discharge and that it has had ongoing physical, spiritual and mental implications for those who can no longer trust either doctors or priests.

This is an appropriate point to introduce the evidence of suffering of LGBT personnel serving under military law in the replies to the call for evidence. 1,128 responses were received in response to the Call for Evidence. These included: 301 from veterans who were dismissed or discharged because of LGBT same-sex sexual acts or sexual orientation, whether pursuant to a court martial or by way of administrative discharge under the Queen’s Regulations, 297 from veterans who felt compelled to purchase their release from their service contracts or otherwise resigned or did not extend their contracts because of the Ban and 416 from those who were not LGBT but witnessed the implementation of the Ban.

The responses to the Call for Evidence forms a unique body of evidence describing the shameful and devastating impact on those who had signed up to serve in the Armed Forces for the good of the nation, and to lay down their lives if need be

Many found it a painful and traumatic experience to relive their experience of what led them to leaving military service and the consequences. Very few of the stories were seen before. They lie at the heart of this Review and its recommendations.

There is nothing more powerful and significant than the words of the LGBT veterans themselves. Although a very small proportion of the total testimony received is quoted in the final report, what is quoted describes the major themes which colour the review and justify the recommendations which I made.

In view of time constraints, I summarise below very briefly the main themes of the responses to the Call for Evidence. I have referred to them summarily earlier. In some cases, I have also quoted from a response. These represent only a tiny proportion of the evidence given to us. They take up 76 pages of the Final Report.

In broad terms, the responses to the Call for Evidence paint a vivid picture of homophobia at all levels of the Armed Forces during the period 1967 to 2000 and the bullying that inevitably reflected it. There are numerous factual accounts of the way that the Ban enabled male and sometimes female personnel, whether or not officers, to commit sexual assaults and harassment and escape disclosure by threatening to report the gay victim with the consequence of investigation and dismissal. Victims of predatory and sexual misconduct, especially those who were LGBT, were most susceptible to that blackmail.

In terms of abusive conduct towards military personnel who were perceived to be homosexual, particular note must be taken of the references in the responses to the Call for Evidence to medical internal body examinations of both men (anal probe) and (more rarely) women and other degrading tests as part of the investigations. There was also a frequent requirement to see a psychiatrist. Veterans’ testimonies confirm that conversion therapy was routinely either carried out or proposed as a “cure” for homosexuality. Such therapy comprised both electro-compulsive treatment and drug use. In many cases there was a suggestion that, if personnel consented to conversion therapy, they might be permitted to remain in military service. These abhorrent medical practices unsurprisingly left personnel severely traumatised.

Bizarre as it may seem, these practices extended to those who were perceived to be gay but were not in fact. That was pursuant to policy.

The humiliation was compounded when medals were required to be handed over, or a commission had to be surrendered or there was a demotion in the rank of those who were not officers. Often, particularly where the veteran came from a military family and was not ‘out’ to his or her family, the dismissal or discharge caused a rupture in family relations which endured for a considerable time and sometimes was never healed.

LGBT veterans who were dismissed or discharged because of the Ban talk of an enduring feeling of shame and low self-esteem. Some ended their life through suicide. Many of them attempted to do so or had suicidal thoughts. In many cases, either the fact that the veteran had been dismissed or discharged or the mental ill-health from the trauma they suffered caused them difficulties in obtaining and then successfully continuing in, or obtaining promotion in, employment. For that reason, many of the veterans have had continuing financial difficulties. Many have had difficulty in forming long-term relations or in being open about being LGBT. Many entered into a spiral of long-term depression, drugs and alcohol abuse and compulsive gambling. Some have been diagnosed recently as having or having had PTSD.

A large proportion of those who were dismissed or discharged because of the Ban or resigned or did not renew their contracts because of the stress caused by the Ban had had no contact with veterans organisations. Many never consider themselves veterans in view of the way they were treated. Others encountered homophobia when they sought to engage with veterans organisations. Others did not wish to risk encountering such homophobia or (especially in the case of lesbian veterans) did not wish to be associated with male veterans in view of abuse they suffered from male military personnel when they were serving in the Armed Forces.

There is not sufficient time to set out many quotations in the Final Report taken from replies to the Call for Evidence. They fall broadly within the following categories.

Homophobia

This is, literally, an intense dislike or even hatred of LGBT people. As one respondent said: “the services is the most homophobic environment I’ve ever encountered. I served in the Royal Navy and shore establishments. The hatred for homosexuality was institutionalised.”

Bullying, blackmail and sexual assaults

“Only became aware of being LGBT after joining”

Absence of pastoral care.

I have already addressed this.

Those perceived to be gay

“I was branded as gay, but I wasn’t. I ended up in a fight with another soldier. The military police came and arrested me. No idea what for. Two days I spent in jail … Then taken to the camp commander who told me that we don’t have gay men in the army I wasn’t able to express my story and was told I was to be discharged that day … This shattered my dream to be a British Soldier which I dreamt since I was 12”

Denial of promotion, promotion held back

Abusive investigation and discharge

“I was escorted for interview by the SIB and was interviewed for eight hours continuously and I was not allowed to access the toilet during that time. I was told I would get to access a toilet only when I admitted to being gay”

“I was arrested in the meeting and then questioned for more than a day. Two SIB police officers questioned me in immense detail about what had happened and were most interested in my sex life. They asked many questions about the precise details of the sex that I had had, with graphic and detailed answers required about penises, rectums, fingers, STDs, people I knew or thought to be gay.”

Medical intervention as part of the investigations and discharge procedures

I have already addressed this.

Medals and conduct badges taken away or not awarded, demotion in rank

Voluntary termination of service due to the strain and service personnel having to hide their sexuality

“It was a constant source of stress having to hide my sexuality and knowing that the slightest mistake could lead to the most unpleasant outcomes. It meant that I became used to hiding feelings and emotions. It meant that I became used to lying in vetting interviews and with colleagues, superiors and subordinates. It meant I had to damage others in order to enhance the image that I was straight, for example by leading girls to think that I was interested in them so that I would have companions for social events and then dumping them when the relationship became inconveniently close…. Overall, it was extremely damaging for my self-esteem and I left in 1980 after 13 years service because I could not see how I could possibly pursue a successful career that my superiors seemed to think I was cut out for whilst being under an increasing microscope of scrutiny as I became more senior. Above all, I was deeply unhappy in the career that I loved and had been determined to pursue from the age of 14”

Shame and loss of self esteem

“I lost everything including my self-worth, esteem and dignity”

Effect on mental health

“The whole process has left me traumatised and suffering from PTSD. I have been left with suicidal thoughts, and have not been employable, and therefore have had to work for myself having had in excess of 40 different jobs. The whole experience has left me with paranoia, and I still have nightmares about the time leading up to my discharge. I have lost two houses I have owned as a result of my instability, and am currently renting… It left me feeling suicidal, to the extent that I moved to Bristol to be nearer to the suspension bridge in case I decided to kill myself… I have gone from being an incredibly happy go lucky type of guy before being thrown out of the RAF to suffering from anxiety, panic attacks and paranoia.”

Attempted suicide, suicidal thoughts

Effect on family relationships

“I was forced to come out to my parents. I experienced abuse from my dad… I was rejected by my dad and brother and have no family because of who I am”

Homelessness, employment and financial difficulties

“I was made homeless by my parents as they couldn’t afford to keep or accommodate me. I was put on the dole and sobbed in the job centre when asked why I had left. I was discriminated against by my future employers when I told them at interview why I left the Royal Navy. I experienced decades of undiagnosed depression, now clinically recognised and diagnosed as PTSD. I could not settle into the workplace and still can’t. I had learned at a young age not to be myself and to hide. I hide from social events. I did not go to a community like I had in the Navy. I have spent 30 years being bounced from city to city due to mental health and fear of being “found out” or react to other discriminatory experiences which act as a memory trigger. I lose the job and then cannot get benefit to pay rent. I am 51 years old. I have lived in six cities in the last five years. I have no friends and, despite having got into massive debt, I have not found a career I like or want. The Royal Navy was all I ever wanted to do”

How did it come about that the Ban was lifted in January 2000?

In 1991 a mutual support group of and for those who had been dismissed from the Armed Forces on the grounds of homosexual acts or orientation was formed on the initiative of former Lieutenant Elaine Chambers of Queen Alexandra Royal nursing Corps and former Warrant Officer Robert Ely of the Parachute Regiment. It was called Rank Outsiders. They were in due course succeeded as chair by Lieutenant Commander Patrick Lyster Todd.

Initially, activities were restricted to providing advice and support for those involved in “live” cases and providing companionship in a social space for those who had left the Armed Forces sometime earlier. A helpline was installed in Stonewall’s offices, which functioned for one or two evenings each week, when members of the Armed Forces facing investigation or arrest could call for help and advice.

By 1994 there were those within Rank Outsiders, especially Edmund Hall, a former Sub Lieutenant in the Royal Navy, who wanted to make the lifting of the Ban a major part of the group’s aims.

In addition, in the spring of 1995 Duncan Lustig-Prean, who had been a Lieutenant Commander in the Royal Navy, was appointed to a new post of campaigns and political director. In that capacity, and as vice chair of Rank Outsiders, he commenced actively campaigning with Ed Hall in the media, Parliament and the MoD.

The Armed Forces Legal Action Group was founded by Ed Hall in 1993 to end the Ban on gays and lesbians serving in the military. The first meeting was in 1994. Stonewall lent support in allowing their offices to be used for the initial meetings. By the end of 1994 Ed Hall had finished writing a book on the Ban “We can’t even march straight” (subsequently published in May 1995). The objective was then to look for the best cases to bring before the courts.

I have mentioned already several LGBT veterans, who served under the Ban and were trailblazers for justice. I will mention others later in this lecture. You will probably never have heard of them and doubtless will not remember them in the future. I refer to them out of respect. They lit the torch that ultimately led to the Review and my Final Report and the government’s acceptance of its recommendations. They were people whose courage and determination led the way to justice for LGBT veterans who served under the Ban and whose initiatives have changed the way that LGBT military personnel are treated in the Armed Forces today. In the debate in the House of Commons on the Review on 12 December 2024, Al Carns MP, the Minister for Veterans and People, who was a former Royal Marines Colonel and received the Military Cross said:

“I have an old saying from combat: “courage is a decision, not a reaction”. Few have been so courageous as those watching this debate today. To stand up, to struggle to your feet when everyone is trying to push you down, and to shout when everyone is trying to silence you-that is an active decision and, and perhaps the most courageous of all. They should stand proud from here on out”.

Returning to the litigation history.

Bindmans solicitors were willing to give support and Stonewall and Liberty agreed to provide funding for judicial review of the four leading cases that were eventually selected. Those cases were in the name of Duncan Lustig-Prean, John Beckett, Jeanette Smith and Graham Grady. They had served in the Armed Forces and had exemplary military records. They were each discharged pursuant to the Ban on various dates between 1993 and 1995 because of their sexual orientation.

Each of them applied to the High Court to quash the discharge as unlawful. Their applications were dismissed by the High Court in 1995, and their appeals were dismissed by the Court of Appeal. The Judicial Committee of the House of Lords refused permission to appeal to the House of Lords.

The applicants then applied in 1996 to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. They applied on several grounds of alleged breaches of the ECHR, but their most important submission was that the investigations into the homosexuality of the claimants and their administrative discharge on the sole ground they were homosexuals constituted a violation of the claimants’ right to respect for their private life under article 8 of the ECHR.

The European Court of Human Rights published its judgements in favour of the applicants in September 1999. On 12 January 2000 the Secretary of State for Defence announced the end of the Ban.

Subsequently, the European Court of Human Rights awarded “just satisfaction” to each of the applicants.

Following the success of the European Court of Human Rights cases, the Treasury Solicitor set about reaching a settlement of other outstanding cases. There was no compensation scheme set up by the government applying the principles implemented by the European Court of Human Rights. There were merely negotiations to compromise each case that had previously been commenced. Potential new claimants were sometimes told that it was too late to start proceedings and in other cases they were told simply that they were not entitled to compensation. The replies to the Call for Evidence show that most LGBT veterans who served under the Ban were unaware of the European Court of Human Rights cases or of any right they had ever had or might still have to claim compensation.

In 2017 and 2018 Craig Jones, who had served as a Lieutenant Commander in the Royal Navy under the Ban gathered together a group of LGBT veterans who had served under the Ban with a view to the publication of their stories and his. The result was that in 2019 a book, edited by Jones, containing 10 accounts by Jones and other former LGBT military personnel, with a foreword by Admiral Lord West GCB, DSC, PC, was published under the title “Fighting with Pride – LGBTQ in the Armed Forces”. (Recently updated anthology, “Serving With pride”)

Three contributors to the book – Jones, Caroline Page (formerly a Flight Lieutenant and the first openly serving transgender officer in the British Armed Forces) and Patrick Lyster-Todd conceived the idea of forming a charity to support and achieve justice for LGBT veterans who had served under the Ban. To that end, Fighting With Pride, the UK.’s only LGBT+ military charity, was registered in October 2020 as a charitable incorporated organisation. In short, FWP was conceived as an organisation to promote restorative justice, celebrating Rank Outsiders, the Armed Forces Legal Challenge Group and the many individual veterans affected by the Ban.

In December 2019 Jones met the OVA Minister, Johnny Mercer MP, to argue the case for restorative justice for LGBT veterans.

In November 2021 FWP secured for the first time participation for LGBT veterans to march in the national service of remembrance in London as an LGBT contingent. Without the campaigning by FWP and discussion between Jones and Johnny Mercer MP the LGBT veterans independent review would never have taken place

Before turning to my recommendations in the final report, I should mention the Canadian LGBT “Purge” Final Settlement Agreement (“the FSA”) as it provided a very useful comparator in some respects. The FSA was a court approved settlement of a class-action commenced in 2017 against the Canadian government in respect of those members of the Canadian Armed Forces, Canadian mounted police and employees of the federal public service who had been subject to anti-LGBT government policies and actions.

In the final Report, I made 49 recommendations for implementation by the government. All of them have been accepted in substance. There were also recommendations in relation to veterans organisations and non-governmental organisations, housing and the devolved administrations. There is no time to consider these last groups of recommendations.

Turning to the recommendations to government, limitations of time require me to concentrate on just some of them.

My first recommendation was that the Prime Minister should deliver an apology in the UK Parliament on behalf of the nation to all those LGBT service personnel who served under and suffered from the Ban (whether or not they were dismissed or discharged). It was extremely difficult to secure this, possibly the most important, recommendation. Access to Prime Minister of the time, Rishi Sunak, was obstructed by the existence of policy advisers, military advisers and many other Cabinet office personnel. In the event, I myself only became aware that the Prime Minister would give an apology in Parliament the day before it was given.

I recommended that there should also be individual letters of apology from the head of each of the Services to LGBT veterans who served under and suffered from the Ban and applied for restitution.

Commission and rank should be retrospectively restored to what it was immediately before dismissal or discharge where there was a demotion.

I recommended that all the LGBT veterans who served under the Ban should receive the Armed Forces Veterans Badge, that medals which were required to be handed back on dismissal or discharge should be restored, campaign and other medals to which an LGBT service person was entitled but which were withheld during and following investigation and discharge should be awarded, berets should be replaced, and there should be designed and granted a special veterans badge for all those who served at the time of the Ban.

I recommended that each Service should arrange for one or more ceremonies of Restoration and Restitution to be made unless the veteran expressed a wish for such Restoration and Restitution to be conducted privately.

One of my recommendations to government, which I considered to be particularly important was a permanent memorial to LGBT past, present and future military personnel to mark their service and their treatment.

I also recommended an appropriate financial award to be made to affected veterans, notwithstanding the expiry of litigation time limits. There has been much debate about this recommendation.

I made a number of recommendations about the delivery of healthcare to LGBT veterans.

Considerable progress has been made in the implementation and delivery of the recommendations.

A structure has been set up for financial payments, and it is anticipated that payments will start to be made during the course of this year. The government’s scheme, which it calls a financial recognition scheme, has a total budget of £75 million. The scheme provides two types of payment to recognise the discrimination and detriment suffered by LGBT personnel under the Ban. The first is for those who were dismissed or discharged. This will be available to veterans who were dismissed or administratively discharged, including officers instructed to resign because of their actual or perceived sexual orientation or their gender identity under the Ban. The payment will be at a flat rate of £50,000. The second is for those who were impacted in other ways. It is open to all those who experienced pain and suffering under the Ban, including harassment, intrusive investigations and in some cases imprisonment. The impact payment will be assessed by an independent panel, with tariffs ranging between £1,000 and £20,000 to tailor the award to each individual. Payments, therefore, can reach up to a maximum of £70,000 for those who are most impacted and most hurt and qualify for both awards. The scheme will remain open for two years, and applications for payments from the scheme from terminally ill veterans will be prioritised. The scheme officially opened on Friday, 13 December 2024. The government has allocated £90,000 to help charities assist the veterans with their applications. There is to be a reverse burden of proof in relation to claims to the £25 million element of the scheme.

Inevitably, the amounts payable under the government’s financial recognition scheme have been criticised by some as too low. On the other hand, for many LGBT veterans who served under the Ban, no amount of money can ever provide sufficient compensation for their suffering. In addition, the relatively modest amounts have enabled the financial recognition scheme to be devised and implemented much more quickly than, for example, amounts payable under the Infected Blood investigation, the Horizon investigation and Grenfell.

The memorial to be erected at the National Memorial Arboretum has been designed and takes the innovative form named “An Opened Letter”, reflecting the conduct of SIB investigations when personal and private letters, diaries and other material were taken and never returned even if the investigation did not lead to dismissal or discharge.

An enamel ribbon has been designed to be worn on civilian clothing by all those LGBT military personnel who served under the Ban. It is in the colours of each of the three services, with the insignia of all the Armed Forces in the centre surmounted by a crown. It carries the motto “superbia” and “justitia”- pride and justice. I was not involved at all in the design and production of this badge. I was deeply touched when those who were responsible, in consultation with others, decided that it should be called the “Etherton Ribbon”.

There is no doubt that the review, the final report and the implementation of my recommendations has changed the lives of a great number of LGBT veterans. So many of them now say that they no longer feel worthless or culpable in some way and that their pride in their past military service and their association with the other members of the Armed Forces have been restored.

The one group which appears to have been and still is suffering from significant ill treatment is women and especially LGBT service women. Considering that women military personnel have never exceeded 12 percent of those subject to military law, the ratio of female to male veterans who identified as homosexual or were perceived to be such and responded to the Call for Evidence is as I have said, notably high at 61:39. It is clear that considerable misogyny continues in the Armed Forces today. The death of the Royal Artillery Gunner Jaysley Beck, found dead at 19 years of age at Larkhill Camp, Wiltshire in December 2021 is a notable recent event. Some research is underway on this issue.

There are very, very few occasions in a person’s life when they are given the opportunity to improve the lives of a significant number of people. The conduct of the review and the writing of the Final Report have enabled me to do so. I feel hugely privileged to have been given and, in some important respects, to have achieved improvement in the lives of LGBT veterans who suffered so disgracefully and so considerably when the Ban continued after 1967.

Our Facebook Live stream

IWM Footage will follow